- Home

- Sameer Pandya

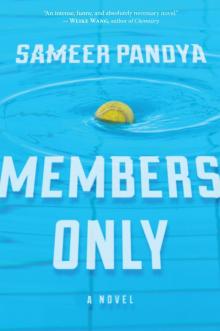

Members Only Page 8

Members Only Read online

Page 8

“That’s a smart point. But that’s why I would spend more time with you. And try to read between the lines. And read beneath the lines. I’m not just taking everything at face value. But sure, there are clear limits to the method. But there are limits to all methods. We recognize that and work from it.”

“Biology doesn’t have limits. Chemistry. Engineering.”

“I can’t speak for the sciences. But there are plenty of scholars who would argue against that. Argue against the idea that a lab is a perfect place of objectivity and equity. How many times have you heard of one study debunking another that had been gospel only a few years before? Coffee is healthy for you one year, bad the next. I keep drinking it no matter what.”

This line of argument seemed to satisfy him; he nodded his head. If only defending the discipline were always this easy.

He rubbed his forehead with his fingers. They were long and lean and quite graceful. “Do you think they pay you enough for the work you do?” he asked.

Where before his eyes had darted around, this time he looked straight at me. And the slightest mocking smile curled up on his face. I worked at a large public university. All of our salaries were public information. For all the fancy degrees I had, it embarrassed me how little money I made. I was sure that Robert had been snooping around online.

“Are you here to discuss my salary?” I asked, trying my hardest not to let the anger and humiliation I now felt appear on my face or in the tone of my voice.

“I guess I was wondering if you feel you’re being properly paid for the hard work you do. My father has never been paid what he deserves, and I’ve always felt sorry for him. He’s worked so hard his whole life. And he has nothing to show for it.” His voice seemed to crack a tiny bit. “I know it sounds a little weird, but he reminds me a lot of you. You both have a similar sense of humor. A little self-deprecating.”

To avoid having to respond immediately, I took another bite of the sandwich—a bite that happened to include an enormous jalapeño pepper. I tried to chew it slowly and swallow, but my mouth was on fire. I could feel sweat forming on my forehead. I couldn’t figure out if Robert wanted to connect with me or if this was some elaborate way of mocking me. That last bit about his father was perplexing. Did he see me as a father figure as well as an object of his pity? I swallowed the pepper and took a long sip of my water before I answered.

“Robert, I appreciate your concern, but if there’s nothing else you’re wondering about the class, I think we’re done here. I’m sure there are students waiting in the hallway.”

I got up from my desk and walked into the hall. “I’ll be just another minute,” I said to a student, then I went back and sat down.

I expected Robert to apologize for having overstepped. But instead he reached down for his backpack and stood up. “Thank you for your time and for sharing your sandwich. That was an interesting lecture today. Something that calls for a further discussion.”

When he walked out, I noticed that I had spilled a dollop of mayo on my shirt. I wrapped up the rest of the sandwich, tossed it in the garbage, and tried to wipe the mayo off.

Another student walked in. He had a shock of blond hair and was dressed in a sweatshirt and shorts. He was wearing the same tennis shoes Federer wore in his matches, with the laces untied.

“Go ahead and sit down,” I said.

“I can’t stay. I have practice. But I wanted to come by and let you know that I won’t be here for the midterm. We have an away match. When can I take it after I get back?”

I didn’t know this student, but I had a pretty clear sense of his life. His tennis skills had been celebrated since he was a kid and now he was convinced that he was headed somewhere big on the court, only to end up with a decent consolation prize: a job in finance after graduation, hired by an older former college tennis player, followed quickly by marriage, kids, an affair, another kid. Right then, as he stood in my office with no perspective, it must have all seemed so open and unknown and possible to him, as if soon enough he’d be wearing his own namesake tennis shoes and some other kid would stroll into some other office wearing them, their laces also untied.

“You’ve known the date of the midterm since the first day of class,” I said. “You couldn’t have come to see me any earlier?” It was a genuine question.

“Things came up.” He was staring at the grease spot on my shirt.

“You can take it before,” I said. “But not after.”

“But I have other stuff going on.”

“So do I. Be thankful that I’m letting you take it early.”

He was speechless, as if this were the very first time anyone had ever said no to him. “I’ll talk to my coach.”

“Feel free,” I said. “I’m sure he can write out some kind of exam for you. But for my exam, I’m the only one you need to talk to.”

We agreed on an earlier date. He left.

I closed my door halfway, reached into the garbage can, and removed the sandwich. It was, after all, fully wrapped. For the next ten minutes, I sat there, finished eating, read ESPN online, and felt good about pushing back with the tennis player. I had a reputation for being overly accommodating to students’ needs.

As office hours were about to end, one last student walked in. This one I also recognized from my large lecture class. He reminded me of myself when I was in college, though he was taller, more handsome, and far more self-assured. So, in fact, he was nothing like me, but for our shared Indianness. He always sat in class with a pretty young woman, whose ethnicity I couldn’t quite make out.

“I’m in your anthropology class. My name is David.”

I was about to ask if that was short for something. I didn’t think this new generation of Indian Americans had gotten in the habit of Americanizing their names.

“It’s just David,” he said. “I get that confused reaction from other Indians all the time. My family is Catholic. That’s actually why I came to see you.”

He had a very inviting smile; it would be much easier for him to navigate the world. A good smile can soften any situation. But as he sat down, he became more serious.

“I was a little taken aback by the last thing you said in class today, about how India fills an absence for Christians, and Westerners more generally.”

I sat up in my chair, to signal that I was paying full attention to him. In turn, David also seemed to straighten his back.

“Maybe ‘taken aback’ isn’t the right phrase. It actually upset me, more than I first realized.”

“Why?”

“I’m Catholic and Indian, but born in Los Angeles. So I guess that statement was confusing for me.”

Here was the type of conversation—full of ideas and mild arguments—I longed for in office hours, and which I seldom was able to have these days. So often, students seemed to treat the ideas I presented to them as static, meant to be regurgitated on an exam and nothing more.

“I can see that,” I said. “But when I make a statement like that, it’s not meant to include everybody and every experience. I have to try and speak to some general experiences about why there has been such a consistent interest in Indian life throughout American history. Today I tried to argue for one way of understanding that interest. But there are always exceptions. You’re an exception.”

David nodded. I couldn’t tell if he was buying this argument or not.

“But are you arguing that Christianity is empty?”

“No, no. I’m arguing that for those Americans who turned away from Christianity, India filled the hole left behind.”

David glanced at his phone. It was buzzing.

“I’m so sorry. I have to take this. But if it’s OK, I’d like to come back on Wednesday so we can talk about this more. I should have come in earlier.”

“Do come back,” I said. “Let’s talk through this. It’s worth a longer conversation.”

David got his things and walked out.

At 12:30, I headed to another

class. And at 2:00, I had yet another. These classes were smaller, forty students each, and because they were more advanced, there was a lot of conversation and back-and-forth with the students.

I was about twenty minutes away from being done with the second class when I took a sip of water and examined my notes to see what else I needed to cover. There were too many voices in my head—the things we’d been talking about in class, Robert asking me about my salary, Suzanne asking me to apologize to the Browns. There were administrative emails I had to respond to, letters of recommendation I had to write. I opened my mouth to resume. The students took notice and readied themselves to write down whatever I was going to say. But nothing came out. The words and the ideas were there, in my head, in my throat, but that’s where they stayed. It was as if a muscle tissue had grown over my mouth; I usually had plenty to say. The students waited.

Then someone in the back started talking about the essay they’d read. And then another student added something else. I let them all talk among themselves.

At 3:15, when I finally got out of my third class, I felt like a bus had hit me. I had talked straight through three, seventy-five-minute sessions, minus those last twenty minutes. Over the course of the day, I had taught nearly three hundred students. Most of them had been engaged and interested. Some of them less so. I felt completely depleted.

As I walked back to my office, my right knee suddenly sore for no apparent reason, I saw Josh Morton again. This time, he was in shorts and a T-shirt that read YALE SWIMMING. His hair was wet. He was clearly in peak physical shape. If he had taught at all today, he had probably had one class, a small seminar with ten or fifteen fully engaged students. I bet if one of them had asked him about his salary, he would have proudly revealed the numbers. He got paid a lot more to do a lot less, at least when it came to teaching. That’s all there was to say about that. With my shoulders hunched and my lower back sore from being in front of the classroom, I felt like I was literally aging faster than him, my step getting slower with every passing day. If indeed we were all living in a state of insecurity, I had to imagine that anyone with the freedom and opportunity to take a long swim in the middle of a workday might be able to manage that insecurity a little better than a prison guard working in a lockup in Tennessee.

* * *

When I pulled into our driveway, I sat for a minute, collecting my strength for the evening.

In the kitchen, napkins, forks and knives, and glasses for water and milk were laid out on the table. There was a pot on the stove. Set tables and family dinners were important to Eva, and I appreciated that. But the late afternoon sun was beating through the window, and as much as I liked the idea of it, I didn’t want to sit where the heat had accumulated through the day.

Eva walked into the kitchen.

“I appreciate your willingness to try,” I said.

“One of these days, we’ll all sit, talk about the day, and eat our meal.”

I started walking out of the kitchen.

“Can we talk now? You’ve been avoiding me all day.”

“I just need a moment to change and gather myself a little. I’ve had a long day of teaching. I haven’t been avoiding you.”

“Some days we talk on the phone five times when you’re at work.”

I got a bottle of wine from the pantry and uncorked it. Eva took two glasses from the cupboard and held them out. I poured.

From the back of the house, I could hear Neel bouncing off the walls, slamming and opening doors, his body somehow too big for the space. Arun, who was much less prone to being hyper, had been swept into his older brother’s lead. The boys had started back at school several weeks before, and things weren’t going well for Neel. And when things weren’t going well at school, things weren’t going well at home.

“They’re fine,” Eva said.

“Let me go check.”

“Stop, Raj. We need to talk about this. This affects us all.”

“No!” Arun shouted at the top of his lungs. He had become an expert at screaming foul at most everything.

“Go ahead,” Eva said, lowering her voice in resignation. She was trapped between the bad behaviors of all of the boys in her life.

We walked into the living room. There were toys everywhere and remnants of school worksheets Neel had started and then abandoned. I liked a neat house and so did Eva, but with these two boys, that was a state of being we wouldn’t return to until they left for college. Neel, especially, had a particular gift for speeding up entropy.

“You want to go?” I asked. “I need a minute and then I’ll be there.”

And again a scream, this time a little different. Eva took one more sip of the wine, set her glass down, and headed back. I tried my best to tune out what was going on in the bedrooms and concentrate on my wine.

“He took it,” I could hear Arun cry. “He took it.”

“I don’t have it,” Neel yelled back. “You asshole.”

Well advanced in his use of curse words, Neel had a tendency to torture his younger brother. And so it was hard to believe that he had nothing to do with the disappearance of whatever had gone missing.

I wanted to let Eva handle it, but I couldn’t pretend nothing was happening. I’ve never been able to drown out the noise. I went to Arun’s room, where the battle lines had been drawn. Both boys were in their underwear and their hair was tangled. The floor was covered with Legos.

“I didn’t take it,” Neel said, turning to me. From the day he was born, there’d been something in his bright brown eyes, some sense that he could see everything and that there was never enough time for him to process it all. Now those eyes were pleading with me to believe him.

Neel was a big, strong boy, with smells and hair just around the corner. He’d grown out of his baby phase quickly, while Arun had lingered in his. Arun was smaller and sweeter, qualities he sometimes used to his advantage.

“What’s the it?”

“A Lego guy,” Neel said. “Darth Vader. And I didn’t take it. But I know you don’t believe me. You guys never believe me. You always believe this little shit.”

Arun was distraught and confused.

“Language, Neel,” Eva said.

“I don’t care. You won’t believe me no matter what I say.”

“Neel, I think you should go to your room,” I said, trying to keep calm. Separating them was the first step toward deescalating the moment.

“I’m not going anywhere,” Neel said, starting to cry, too.

“Please go,” I said. “Let me try and figure this out.”

He finally left. Eva followed him.

For the next twenty minutes, as I helped Arun clean up his room and find Darth Vader, Neel raged across the hall about all sorts of things that didn’t need raging. Dinner, his brother, his room, the curtains, what he could and could not watch on television. All of it accompanied by so many tears. I thought about all the friends I had who had kids this age, and I couldn’t imagine any of them went through what we went through on nights like this. And we had these nights so often.

I took Arun into the kitchen after we cleaned up. Eva had made a stir-fry and I got us two plates of it.

“I’m sorry your brother is so upset.”

“It’s OK.”

Kids’ brains are sponges; I didn’t want Arun’s to be saturated by this chaos.

I watched as he slowly and methodically made his way through dinner, taking small bites and chewing thoroughly. In the corner of his plate, he set aside a pile of mushrooms.

“Want them?” he asked.

I did. They were my favorite part of the meal.

Then we headed for a bath. Arun removed his underwear and got into the warm bath water. I soaped him up and then he went completely underwater to wash it off.

“All done,” I said. “You want to get out?”

He didn’t respond. He got onto his belly. His sweet little bottom bopped out of the water like the top of an apple. I reached over and pinche

d it.

“Stop,” he said sweetly.

“How was school? Are you liking it?”

“It’s fine. Recess is fun. And I’ve been playing the recorder.” He continued to rock back and forth in the water.

“Do you see your brother during the day?”

“At recess sometimes. He walks around by himself.”

I felt sad thinking of Neel by himself in a playground full of laughing children.

“But then I go and play with him,” he continued. “He’s always nice to me at school. He gives me some of the gummies in his lunch after I’ve finished mine.”

“Let’s get out and draw a little,” I said. “Maybe we can make a little note for him.”

He got himself dressed and I pulled out some coloring pens. I could spend hours coloring. It gave me an activity to concentrate on while I let my mind wander. There was something meditative about it. Maybe that’s why Bill Brown kept those beads around his wrist.

“Superheroes or chickens?” Arun asked, holding up two different coloring books.

“You pick.”

He took the chickens. I opened the other book randomly, found the right shade of green among the pens, and started coloring in the Hulk. As I worked, I thought about what I should say to Bill, whether I should email or call or reach out to him in person. The longer I waited, the more nervous I would be in talking to him; I knew that I needed to take care of it as soon as I could. And yet, when I pictured the start of the conversation in my mind, I felt anxious. What exactly would I say? What if he refused to see me at all?

“Get out,” Neel yelled across the hall.

Arun was gone and I hadn’t even noticed. Lately, I’d been losing some of my sharpness, particularly at the start and the end of the day, leaving me with a precious few hours of clarity in the middle. There were many things I found difficult about parenting, but close to the top was having to go through the stresses of my everyday life and somehow put them aside in the evenings, turning my full attention to the needs of the children.

Members Only

Members Only